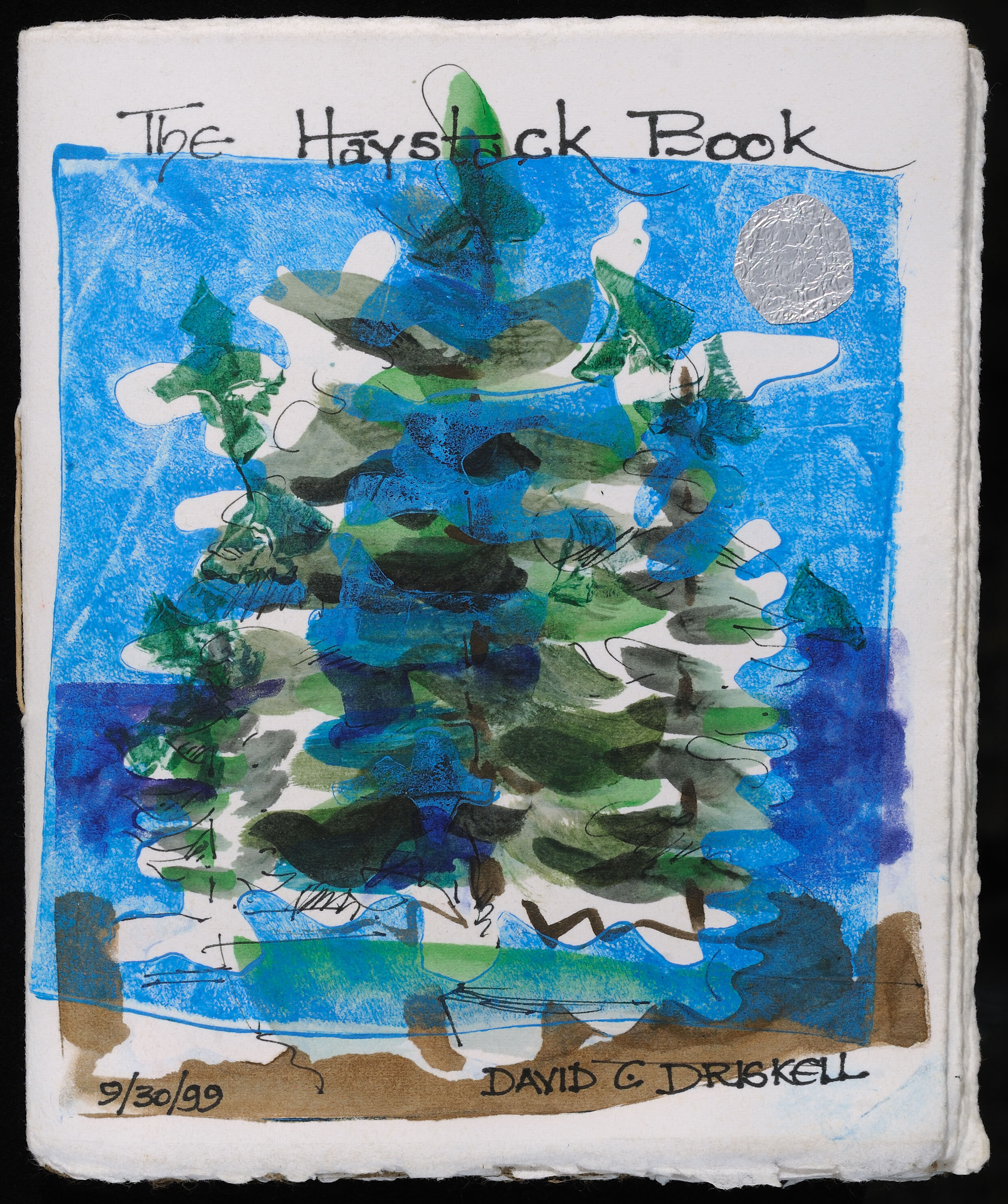

Above: David Driskell, 'The Haystack Book' (detail), September–October, 1999, gelatin print and drawing on paper, 6 1/2 x 10 inches. Photograph by Gregory R. Staley. Collection of and © Estate of David C. Driskell

David Driskell’s beloved icons are drawn from his spirituality, his community, and the landscapes he inhabited. His artwork is saturated with symbols from the natural world, his experience in the South and Appalachia as a Black man, his African ancestry, and the Black Christian church.

KEY TERMS

Archetype – an object or a person that appears repeatedly in stories from around the globe

Candomblé – a religion based on beliefs from different regions in Africa, which is particularly popular in Brazil

Celestial – an object or person relating to the sky or heaven

Composition -the arrangement of visual elements in a work of art

Crucifix –a symbol of a body on a cross. This symbol represents Jesus Christ, who was killed on a cross according to the Christian religion

Cross – a symbol of the crucifix and of the Christian religion

Deity – a god or goddess

Discrimination - when a particular person or group of people are treated unfairly because of their background or identity

Herbalist - a person who heals using plant-based medicine

Icon - a widely known and respected symbol

Racism - when a particular person or group of people are treated unfairly because of their race

Segregation - the separation of some groups of people from others, sometimes because of racism

Soul - the inner being or nonphysical parts of a person that defines a person’s character and is thought to be immortal

Spirituality - deep feelings and beliefs related to the soul and/or religion

Symbol – an object or a living being that stands in the place of another idea, a person, a place, or object. For example, a flag is a symbol for a country

Yoruba – an ethnic group that inhabits western Africa

*note that icon and symbol will be used interchangeably within this guide

ICONOGRAPHY IN THE EXHIBITION

“I think an artist is able to extend himself through the spiritual element when he deals with the symbolic presence of form.”

“I am the quilter that my mother was. I am the builder, the gardener, and farmer that my father was. In my biblical subjects, I am the preacher my father and grandfather were. I am a sophisticated country bumpkin.”

AMERICANA

Driskell notes the American flag’s “capacity to inspire contradictory associations.”

Elements of the American flag can be found in many of Driskell’s artworks. Where do you find these elements of the American flag? What associations come to mind? Are any of them contradictory, or the opposite of each other?

David C. Driskell (United States, 1931–2020), Ghetto Wall #2, 1970, oil, acrylic, and collage on linen, 60 x 50 inches. Portland Museum of Art, Maine. Museum purchase with support from the Friends of the Collection, including Anonymous (2), Charlton and Eleanor Ames, Eileen Gillespie and Timothy Fahey, Cyrus Hagge, Patricia Hille Dodd Hagge, Alison and Horace Hildreth, Douglas and Sharyn Howell, Harry W. Konkel, Judy and Leonard Lauder, Marian Hoyt Morgan and Christopher Hawley Corbett, Anne and Vince Oliviero, D. Suzi Osher, Christina F. Petra, Karen and Stuart Watson, Michael and Nina Zilkha, and with support of the Freddie and Regina Homburger Endowment for Acquisitions, and the Emily Eaton Moore and Family Fund for the Collection, 2019.16. Photograph by Luc Demers. © Estate of David C. Driskell

David C. Driskell (United States, 1931–2020), Shaker Chair and Quilt, 1988, encaustic and collage on paper, 31 3/8 x 22 5/8 inches. Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine. Museum Purchase, George Otis Hamlin Fund, 1990.2. © Estate of David C. Driskell

Chairs are one everyday object that you might notice in some of Driskell’s paintings. Straight back chairs were often in the homes of the rural South, and were used as thrones to emphasize the sacred power of women. Driskell also collected Shaker furniture as his studio was near Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village.

Look for other everyday objects within the artworks. Which objects are familiar to you? Why do you think Driskell might have chosen to paint them?

RELIGION

Angels and wings appear in many of Driskell’s artworks. His father was a Baptist preacher who often talked about angels in his sermons. Driskell pays tribute to the Black Baptist Church through Christian symbols; titles that reference spiritual songs; and compositions that reference Christian architecture and design.

As you go through the exhibition, where do you notice the influence of religion on Driskell’s artwork?

David C. Driskell (United States, 1931–2020), Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, 1972, acrylic on canvas, 50 x 36 inches. Tougaloo College Art Collections, Tougaloo, Mississippi. Purchased by Tougaloo College with support from the National Endowment for the Arts, 1973.084. Photograph by Mark Geil. © Estate of David C. Driskell

David Driskell (1931-2020) Behold Thy Son, 1956, oil on canvas, 40 x 30 inches. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington, DC. © Estate of David C. Driskell

Driskell grew up in the South when it was legally segregated by race. His iconic paintings of the crucifix pay homage to the life of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old Black boy who was brutally murdered by a group of white people in 1955. Till’s murder brought national attention to racial violence and injustice.

In other artworks, how do you see Driskell grappling with, or thinking about, racial segregation and violence?

NATURE AND GEOMETRY

“Thank God for the pine.”

Many of Driskell’s paintings are celebrations of nature and he saw his garden in Falmouth, Maine as a spiritual place. He painted animals and plants such as pine trees, ferns, and snakes. What do you think of when you see these symbols of nature? What do you think these symbols of nature represent?

Driskell began to paint the Eastern White Pine, Maine’s state tree, when he first went to Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture in Central Maine in 1953. What might this tree be a symbol for?

David Driskell (1931-2020) Two Pines #2, 1964, oil on canvas, 48 x 36 inches. High Museum of Art, Atlanta. Gift of David C. and Thelma G. Driskell, 2000.203. © Estate of David C. Driskell

David Driskell (1931-2020) Pine and Moon, 1971, oil on Masonite, 47 3/8 x 35 1/8 inches. Portland Museum of Art, Maine. Museum purchase with support from the Friends of the Collection, 2011.4. Photograph by Luc Demers. © Estate of David C. Driskell

Symbolic circles abound in Driskell’s art, both as subject and compositional shapes. Sometimes they appear as celestial orbs (suns and moons). How many circles can you count in his works? What feelings, associations, or memories does the circular shape bring up for you?

Stripes and strips are a reoccurring visual pattern in Driskell’s art. They represent things that grow. What kinds of plants do you notice in his art?

“I think there is something very special about the Southern Black experience . . . . One of my heroes of the Southern experience is a Black artist, Romare Bearden.”

Driskell’s family were farmers. His paintings feature vegetable gardens with foods from the South such as collard greens, sweet potatoes, okra, and pole beans. His paintings of walnut and pecan trees were made with the plant-based inks that he created.

AFRICA AND THE AFRICAN DIASPORA

“I am interested in keeping alive some of the potent symbols that have significant meaning to me as a person of African descent.”

Symbols present in Driskell’s artworks appear as some combination of compositional elements, subject matter, patterning, and material choices. Quilting and African textile designs influenced the composition of many of his collages as well as his paintings. He was inspired by stripweave, a technique practiced by his mother, Mary Lou Cloud Driskell. In African strip weaving, many thin strips of cloth are woven together to produce fabric. Stripweave is made in West Africa from handwoven fabric such as kente cloth from Ghana.

In which artworks do you see the influence of quilting and/or African-textile designs? What are some of the visual similarities between these artworks and quilting?

David C. Driskell (United States, 1931–2020), Memories of a Distant Past, 1975, egg tempera, gouache, and collage on paper, 21 1/2 x 16 inches. Collection of Joseph and Lynne Horning, Washington, DC. © Estate of David C. Driskell, courtesy DC Moore Gallery, New York

David Driskell (1931-2020) Self-Portrait as Beni (“I Dream Again of Benin”), July 13, 1974, egg tempera, gouache, and collage, 17 x 13 inches. High Museum of Art, Atlanta. Purchase with David C. Driskell African American Art Acquisition Fund, 2015.74. © Estate of David C. Driskell

Inspired by his travels to Benin, Ghana, and Nigeria, Driskell incorporated symbols such as masks into his artwork. Mask-like faces express the power and continuing presence of the ancestors. How might you describe the masks you see in some of Driskell’s artwork? In Yoruba religion, the head is understood as a symbol of “ori inu,” the inner being or soul of a person. How would you describe the soul of the masks you see?

Driskell frequently visited the city of Salvador in Bahia, Brazil, with fellow scholars and artists. The centuries-old traditions of Candomblé informed much of the African diaspora symbols present in his collages. Examples include his depiction of Ohsun (flowers) in yellow and pink; Yemanja (waves) in a deep blue color. In which artworks do you notice the use of these colors?

FIGURES

Some archetypes in this exhibition include peace angels, farmers, and herbalists. Driskell also depicted the Yoruba deity Shango, who controls lightning and thunder. Shango’s common or recognizable symbols include the double-edged axe and curved dance wands (oshe shango), which represent lightning.

Do the archetypes you find in this exhibition remind you of any stories from your culture or your family history?

David C. Driskell (United States, 1931–2020), Woman with Flowers, 1972, oil and collage on canvas, 37 1/2 x 38 1/2 inches. Art Bridges, Bentonville, Arkansas, AB.2018.3. © Estate of David C. Driskell

David Driskell (1931-2020) Night Vision (for Jacob Lawrence), 2005, collage and gouache on paper, 16 1/2 x 22 inches. Collection of Richard and Barbara Schiffrin, Wynnewood, Pennsylvania. Photograph by Sandra Paci. © Estate of David C. Driskell, courtesy DC Moore Gallery, New York

There are several self-portraits in this exhibition; which icons do you see in his self-portraits? What stories do you think these icons tell about Driskell? What icons would you use to tell your story?

Driskell painted a series celebrating Black women. He also paints the Yoruba Orisha deities and elder female priestesses. Notice how he depicts their face, lips, and eyes.

What qualities do Driskell celebrate in these women? What other symbols do you see in these images?